This is the final entry of our banned books triptych. I’d wanted to talk about this in my previous post, but I got a little carried away and couldn’t find a good place for it. (tl;dr: “This is America. You want to live in North Korea, you can live in North Korea. I don’t want to. I want to live in America.” – Ron Swanson)

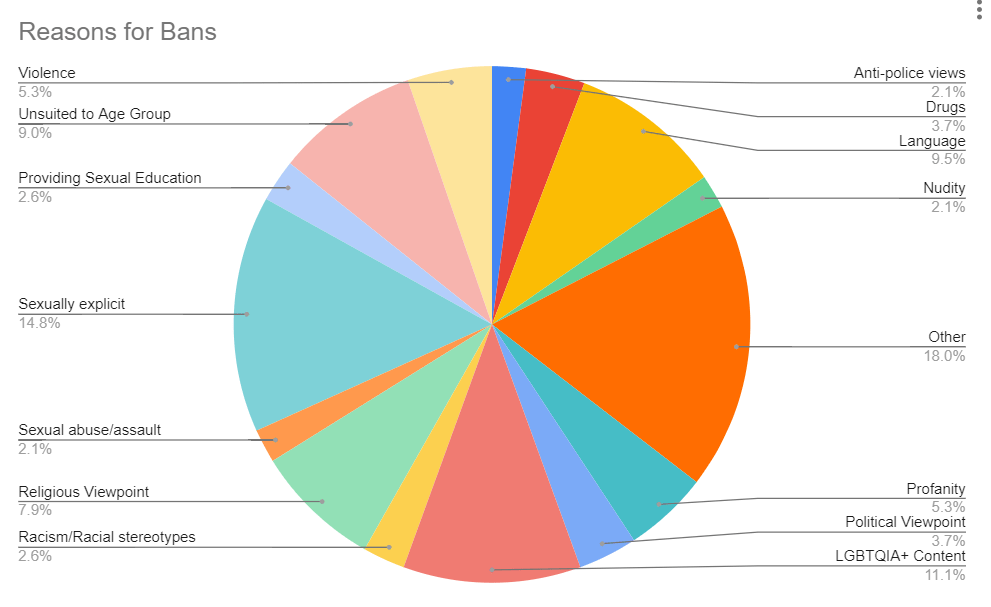

Now we come to the most common reason books have been challenged or banned: that strange, nebulous category of “other.”

And let me tell you: “other” is wild. Some of my favorite reasons given include a book using the phrase “poo poo head” (Super Diaper Baby by Dav Pilkey) and the Harry Potter books for having real curses and spells.

The curses and spells used in the books are actual curses and spells; which when read by a human being risk conjuring evil spirits into the presence of the person reading the text.

Rev. Dan Reehill

I am extremely disappointed. In the many years I’ve been reading Harry Potter, I have never once summoned an evil spirit. Not even by accident. And if those are real spells in the book, there must be a hell of a delay effect on them. There’s a few people that have overdue Avada Kedavras coming for them.

But most of the “other” reasons given are way less amusing. You can read my list here, or check out the ALA’s list of most challenged books to see reasons why books were challenged. There’s a lot to go through, so I’m only going to discuss a few here. Specifically, the ones that really grind my gears.

Think of the children!

Books that will, somehow, damage children if they read it. This is the justification that book challengers use all the time. Some of the books whose challenges fall under this broad category are:

Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin (2015, 2019, 2021) for the effect it would have on young people

A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo by Jill Twiss (2018, 2019) – “designed to pollute the morals of its readers”

Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James (2013, 2015) – concerns that “teenagers will want to try it”

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck (2020) – negative effect of slurs on students

Prince and Knight by Daniel Haack (2019) – would lead to confusion, curiosity, and gender dysphoria

Some of these are valid concerns. I wouldn’t want teenagers reading Fifty Shades of Grey. Classics like Of Mice and Men, Huckleberry Finn, and To Kill a Mockingbird have all come under fire for racial slurs and stereotyping, and those are fair criticisms. When I read Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird for English class in high school, my teacher addressed the issue head-on. He told the class that these books had slurs in them, and we were going to discuss the language in the book. He also made it clear that we were not to use those words outside of book discussions. Whether this had any impact on the language the students used outside of class I couldn’t say; I didn’t hear many racial slurs being thrown around before or after we read those books. But my high school was also pretty homogeneous, with White Catholic kids as far as the eye could see. In a more diverse school, I can see how books with slurs could be a problem.

I still love To Kill a Mockingbird, though it’s important to acknowledge its failings: White savior, slurs, and false accusations of rape. When I encountered these criticisms, it forced me to re-evaluate the novel and think about it from different perspectives. Yes, it is problematic. Does that mean it belongs in a classroom? At this point, I think there’s enough literature available by people of color telling their own stories that it can be reasonably replaced with something more relevant and less patronizing to students of color.

Does that mean it should be removed from schools or public libraries?

My answer should be pretty obvious. I say no. With each (worthy) critique I found of Mockingbird, it made me understand the text in a new way and look at it with a more critical eye. It’s important to revisit the classics and look over what made them great, what makes them not-so-great today, and what value they still have in the modern day. Turn those not-so-great things into discussions and teachable moments, and use them as an opportunity to practice critical thinking on something that is pertinent to today’s reality.

Most of the other cries to “think of the children” are not so well-intentioned. As you can see in the examples given here, would-be book banners fear that kids will be exposed to anything that isn’t heterosexual and cisgendered. It’s anti-LGBTQIA+ fear mongering coming from deeply misinformed individuals at best and outright bigots at worst. Reading a book where two men fall in love is not going to make anyone gay any more than reading a book where a man and a woman fall in love will make them straight. It’s so obvious that I shouldn’t even need to say that, but here we are. That fear alone is homophobic and transphobic, as it implies that being queer or nonbinary is lesser or undesirable.

Even without that baseless fear, these “concerned parents” don’t want kids to see LGBTQIA+ content because…well, because. Because their religion tells them it’s wrong, or because the subject makes them uncomfortable, or because they’re simply afraid of stories that introduce experiences that are different from their own.

Censoring, challenging, and banning books with LGBTQIA+ content hurts kids. It hurts queer, questioning, and nonbinary kids who need to see themselves in media, to know that they aren’t alone. For straight, cisgender kids, they can learn empathy and become allies. Many who want LGBTQIA+ books out of school libraries cite “parental rights,” saying that parents should be able to decide what books kids can and can’t read. But what a few parents want can’t speak for every parent. Parents – especially those who have LGBTQIA+ kids – may want their kids to read books that others are fighting so hard to take away. A few parents cannot and should not speak for an entire community.

Instead of “think of the children,” let the children think for themselves.

This book is indoctrination!

Of the books that I looked at, there were only two books that were explicitly accused of indoctrinating their readers: The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, and Prince and Knight by Daniel Haack and Stevie Lewis. But books are frequently challenged because they are perceived as promoting some kind of agenda, be it religious, political, or something else. The word “indoctrination” might not be in a book challenge itself, but the fear of it is there.

Some of the books that this would apply to:

And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell, Justin Richardson, and Henry Cole (2012. 2014, 2017, 2019) – “promotes the homosexual agenda”

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon (2015) – atheism

The Kite Runner by Khalid Hosseini (2012, 2014, 2017) – promotes Islam; would “lead to terrorism”

Melissa by Alex Gino (2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020) – encouraged children to change their bodies with hormones

Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds (2020) – using “selective storytelling incidents”

Sigh.

I once knew a man who disparaged public schools and universities, saying that all they did was brainwash students. He was homeschooled in a very Christian household, but never stopped to think that what he had learned could also be considered “brainwashing.”* His education was also based on an agenda, but one created by his family rather than the state. He was still being taught what someone else deemed to be important. The things we learn when we’re young stick with us, whether or not they’re explicitly taught.

When you pick up a book that contains information or ideas outside your realm of experience, you can analyze it critically, you can learn from it, you can forget about it, you can close yourself off and reject it. Encountering new ideas and perspectives can be challenging. I’ve certainly experienced that. When I read How to Be Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi, I found myself bristling at some of the content. I had to remind myself that I was reading this book to learn, even if it meant reading things where my knee-jerk reaction was to reject the information.

Books with diverse perspectives are important tools to understand the world and things outside of our experiences. Opening the world up to new ideas and helping readers to think critically about new information is the opposite of indoctrination.

By taking books away from would-be readers (who, in terms of banned books, are mostly youth), you limit the amount and type of information they can receive. If those readers can’t have access to a wide variety of material and are limited to only reading things that are “approved” by one authority or another…

Well, that is what I call indoctrination.

To avoid controversy/Controversial issues

Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin (2015, 2019, 2021) – to “ward off complaints”

Melissa by Alex Gino (2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020) – to avoid controversy

All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brandon Kiely (2020) – “too much of a sensitive issue right now”

Let me say this first: I get it. I’ve only had one real complaint about a book (so far) and it was a little scary. A woman was furious about a Sesame Street board book which showed the character wearing masks and social distancing. Thankfully, she didn’t make a request to remove the book from the library. I only listened to what she had to say and helped her find books for her kids (who, incidentally, were much too old for board books). It shocked me a little bit, but thankfully nothing more came of it.

When it comes to books with controversial topics, I understand taking caution. As I mentioned in my last post, recently libraries have lost funding and even faced threats of violence for materials that they have on the shelf.

Removing materials over challenges that may never happen is a form of self-censorship. I refer back to the ALA Library Bill of Rights, which states, in part:

II. Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.

III. Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment.

I understand the fear of having “controversial” books on the shelves. But I’m also disappointed. Removing or restricting access to these books feels like capitulating to bullies. Granted, maybe there was a real fear of violence in these cases, but it’s frustrating to see. You can’t challenge censorship by removing materials for a “just in case” scenario.

And, finally, the most bonkers reason given to challenge or ban a book comes from Melissa by Alex Geno:

Because schools and libraries should not “put books in a child’s hand that require discussion”

Then what are schools and libraries for?

What are books for, if not to inform and entertain? To introduce new ideas and new ways of seeing the world, even if it’s a view you’re not familiar with? To maybe even learn something new about yourself?

Schools and libraries absolutely should put books in children’s hands that require critical thinking. Books that feed curious brains and answer questions, either with facts or through the lens of fiction. This is the whole point of intellectual freedom.

Intellectual freedom is a fundamental human right, the basis of democracy and free speech.

And anyone who tries to abridge that freedom is a poo poo head.

*Disclaimer: This is just one example of a person I knew who was homeschooled. There are lots of good reasons to homeschool kids, and just because kids are homeschooled doesn’t mean that they’ll be closed off to new experiences.